Key Takeaways

- Anita Yellowhair's boarding school experience: Anita Yellowhair, a Navajo girl, was sent to Intermountain Indian School in Utah as part of a government effort to assimilate Native American children into Western culture. Her experience, marked by language suppression and harsh punishment for speaking Navajo, reflects the broader goal of eradicating Indigenous ways of life.

- Generational trauma: Anita's story sheds light on the broader impact of boarding schools on Native American communities, leading to intergenerational trauma and the loss of cultural identity. The U.S. operated or supported hundreds of Indian boarding schools, targeting Indigenous children and causing long-lasting scars and negative impacts.

- Shifts in boarding school paradigms: Over time, some boarding schools, including Intermountain Indian School, underwent changes and began celebrating Native identities instead of erasing them. The students' agency and activism played a role in reclaiming their cultural heritage, leading to curriculum changes that incorporated Native languages, traditions, history, and cultural activities.

- Anita's resilience and advocacy: Despite her painful experiences, Anita Yellowhair built a successful career as a dental assistant and became an instrument of healing and education. She shares her story with the hope of creating change, advocating for the preservation and teaching of Indigenous languages and cultures.

- Healing and continued efforts: Indigenous communities and allies work towards healing from the legacy of boarding schools, advocating for recognition, reparations, and policies that promote the revitalization of Indigenous cultures and languages. The resilience of Indigenous cultures and the voices of individuals like Anita Yellowhair underscore the ongoing need for justice, reconciliation, and cultural preservation.

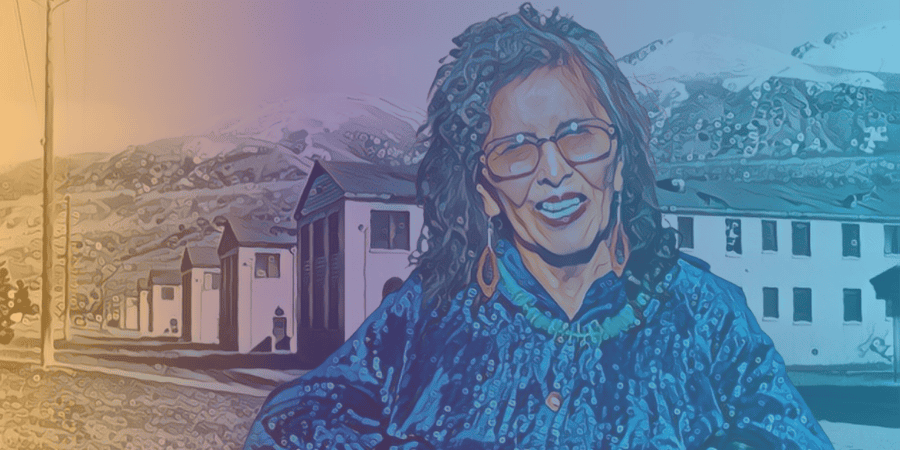

In the year 1950, Anita Yellowhair, a young Navajo girl from Steamboat, Arizona, was sent away from her family’s hogan to attend Intermountain Indian School in Brigham City, Utah.

She embarked on a journey that was a part of a government-sanctioned effort to assimilate Native American children into Western culture, a journey that thousands of other Native American children were also forced to endure.

This abrupt departure from her family and homeland was only the beginning of a decade-long journey that would leave a profound mark on Anita and subsequent generations of her family.

Anita’s life before leaving for school was one of simplicity, with her family relying on sheep for food and traveling long distances for water.

Despite the harsh winters and the lack of modern comforts such as running water and electricity, Anita was content.

She treasured the time spent with her sheep and dogs, taking delight in the sensation of wind on her face as she lay in the fields.

A New World: Challenges of Assimilation

The Intermountain Indian School, which became the largest Indian boarding school in the U.S., was a world away from her hogan and the life she knew.

Upon arrival, Anita, who spoke only Navajo, was required to learn and speak only English, a language she had never encountered before.

Any attempt to communicate in Navajo was met with harsh punishment, ranging from menial tasks like cleaning toilets to kneeling on the floor for extended periods.

Anita’s experience was not unique. Historical accounts reveal that the government and Christian missionaries established these schools in the mid-19th century with the goal of eradicating traditional American Indian ways of life and replacing them with mainstream American culture.

The philosophy behind this assimilation was infamously described by Richard Henry Pratt, a former military officer and founder of Carlisle Indian School, as “kill the Indian, save the man.”

The U.S. Department of the Interior’s May 2022 report revealed that between 1819 and 1969, the U.S. operated or supported 408 Indian boarding schools across 37 states or territories, targeting American Indian, Alaska Native, and Native Hawaiian children.

The Lingering Impact: Generational Trauma

Anita’s story extends beyond her personal experience to highlight the broader impact of these schools on Native American communities.

The forced assimilation and loss of cultural identity has led to what psychiatrists term ‘Indigenous historical trauma’.

This refers to the emotional, physical, and sexual abuse Indigenous people have experienced due to colonization, resulting in long-lasting scars that continue to affect generations.

The U.S. Department of the Interior’s May 2022 report revealed that between 1819 and 1969, the U.S. operated or supported 408 Indian boarding schools across 37 states or territories, targeting American Indian, Alaska Native, and Native Hawaiian children.

The enduring legacy of these boarding schools manifests in the form of intergenerational trauma, cycles of violence and abuse, premature deaths, and other mental and bodily impacts.

Shifting Paradigms: Changing Narratives and Healing

Despite the painful experiences at Intermountain Indian School, Anita managed to build a successful career, becoming a dental assistant after graduating in 1960.

She worked for Dr. Bill Thomas, the only dental officer for the U.S. Public Health Service Indian Hospital at the time, in Winslow, Arizona.

Thomas became a good friend, and Yellowhair taught him about her culture, becoming a part of his family.

The Intermountain Indian School, which closed in 1984, underwent significant changes over its operational period.

In its later years, the school transitioned from erasing Native identities to celebrating them. By 1975, the renamed school became the world’s largest boarding school, with 3,000 students from over 100 tribes.

This shift shows the agency and activism of the students, who gradually reclaimed their cultural heritage, asserting their identities and rights within the school.

This change was indicative of a broader societal shift, as the civil rights movement and changing attitudes towards Indigenous peoples brought about a new era of recognition and respect for Native American culture and rights.

The school started offering classes in Native languages and traditions, and students were allowed, and even encouraged, to speak their native languages.

As part of the curriculum change, the school introduced courses on tribal history and culture, and students were also encouraged to participate in cultural activities, including powwows, traditional dances, and arts and crafts.

Although the initial intent of these schools was to assimilate Indigenous children into mainstream society, the resilience and tenacity of the Indigenous communities, students, and advocates helped to transform these institutions into platforms for cultural preservation and resurgence.

Anita Yellowhair, now an elder in her community, uses her story as an instrument of healing and education.

She speaks about her experiences at the boarding school, not with resentment, but with the hope that her narrative will instigate change and prevent the recurrence of such harmful practices.

She advocates for the importance of preserving and teaching Indigenous languages and cultures, and her story serves as a testament to the resilience and strength of Indigenous communities in the face of adversity.

While acknowledging the historical trauma and the painful legacy of the boarding schools, Indigenous communities and allies continue their efforts to heal from these experiences.

They advocate for recognition, reparations, and policies that ensure the preservation and revitalization of Indigenous cultures and languages.

Their voices, like that of Anita Yellowhair, serve as powerful reminders of the resilience of Indigenous cultures and the need for continued efforts towards justice and reconciliation.