Key Takeaways

- Rising sea levels due to climate change are a significant threat to vulnerable populations, such as the Guna people of the San Blas archipelago in Panama.

- The Guna people's relocation to the mainland is being closely watched as a potential model for other communities facing displacement due to climate change.

- Resettlement involves not only addressing housing issues but also reconfiguring entire societies, including economic, social, and cultural aspects, to ensure long-term success.

- The Guna people's resilience and determination can serve as an inspiring example for other communities at risk, highlighting the importance of preparing for the inevitable impacts of climate change and developing adaptive strategies.

- Diversifying sources of income, such as through handicrafts, farming, and eco-tourism, can provide sustainable livelihoods while protecting the environment.

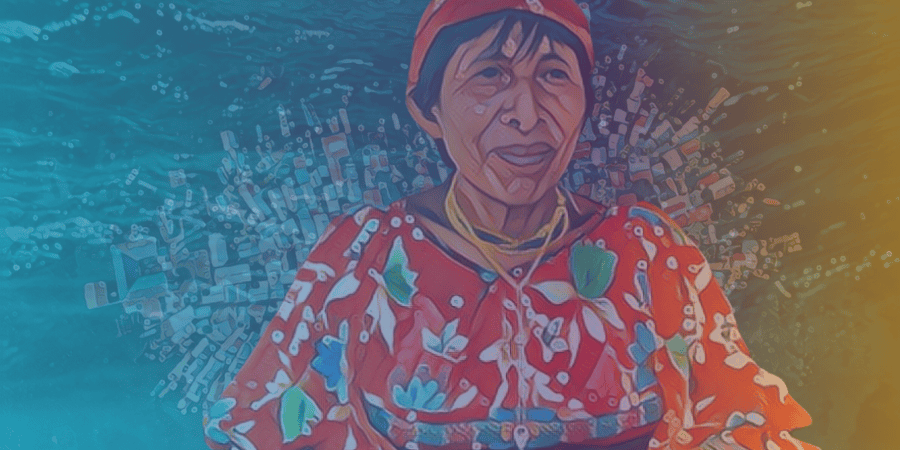

Nestled among the San Blas archipelago, a group of more than 350 islands off the northern coast of Panama, the small island of Gardi Sugdub looks like a vibrant container shipyard from above.

At ground level, it is a hot and overcrowded place, with narrow dwellings packed tightly together, housing over 1,000 people.

The entire island, approximately 150-by-400 meters in size, is gradually being engulfed by rising seas due to climate change.

Resettling the Guna People to Mainland

In a significant move, around 300 families from Gardi Sugdub are expected to relocate to a new mainland community this year.

The resettlement plan was initiated more than a decade ago when the residents realized the island could no longer accommodate the growing population.

Rising sea levels and intensifying storms are exacerbating the situation.

The Indigenous Guna people have resided on these Caribbean islands since the mid-1800s, leaving the coastal jungle area near the current Panama-Colombia border for better trade opportunities and to escape disease-carrying pests.

Now, they are part of the hundreds of millions of people worldwide who might have to abandon their land by the end of the century due to rising sea levels.

A Rising Threat: Sea Level Increase in the Caribbean

In the Caribbean region, sea levels are currently rising at an average rate of 3 to 4 millimeters per year.

As global temperatures continue to increase, this rate could accelerate to 1 centimeter per year or more by the end of the century.

According to Steven Paton, Director of the Physical Monitoring Program at the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute in Panama, all of the San Blas archipelago’s islands will eventually become submerged and uninhabitable.

Climate Change: A Major Driver of Displacement

Anthropologist Anthony Oliver-Smith of the University of Florida in Gainesville has studied people forced from their homes by disasters for over 50 years.

He notes that climate change has emerged as a major driver of displacement, with resource-limited populations being the most severely affected.

The Guna’s Relocation: A Potential Template for Other Threatened Communities

The relocation of the Guna people is being closely observed as a potential model for other endangered communities.

Unlike many others, the Guna have an alternate place to go. More than 30,000 Indigenous Guna live in the Guna Yala province, which includes the San Blas archipelago and a strip of mainland.

Most of them reside on the islands, traveling back to the mainland to collect water from the river mouth and tend to their crops.

Presently, only the residents of Gardi Sugdub are part of the relocation plan.

According to Steven Paton, Director of the Physical Monitoring Program at the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute in Panama, all of the San Blas archipelago’s islands will eventually become submerged and uninhabitable.

A History of Autonomy and Resilience

The Guna people have historically enjoyed a level of autonomy rare among Indigenous populations.

They have successfully defended their cultural heritage, language, and territory over the years.

In 2010, they initiated the resettlement plans and allocated 17 hectares of property on the mainland for this purpose, within the Guna Yala territory.

The Panamanian government is building a school and health center near the allocated land.

The Challenges of Cultural Continuity

To ensure the Guna’s ethnic and cultural identities are preserved during the relocation, they plan to establish programs that teach traditions and culture to the resettled generations.

However, even on Gardi Sugdub, the younger generations appear less inclined to practice traditional customs.

Oliver-Smith is optimistic about the relocation plan but has concerns about how the Panamanian government has approached the resettlement, treating it solely as a housing issue.

He emphasizes that resettlement involves the reconfiguration of an entire society, including its economic, social, and cultural aspects.

Therefore, a comprehensive approach should be adopted to ensure the long-term success of the resettlement process.

A New Life on the Mainland

The new mainland community will have to adapt to a different way of life. While the island residents relied heavily on fishing and trade, they may need to diversify their sources of income on the mainland.

The Guna people are known for their intricate handicrafts, such as the vibrant “mola” textiles, which could potentially serve as an additional source of income.

Farming and eco-tourism opportunities may also be explored, as both activities can provide sustainable livelihoods while protecting the environment.

Learning from the Guna’s Experience

The Guna people’s relocation can serve as a valuable lesson for other communities threatened by climate change.

It highlights the importance of preparing for the inevitable impacts of climate change and the need to develop adaptive strategies, particularly for vulnerable populations.

While it may be too late for the San Blas archipelago, the Guna people’s resilience and determination can serve as an inspiring example for other communities at risk.

By learning from their experience, it may be possible to develop proactive and comprehensive strategies for resettlement that take into account not only the physical challenges of relocation but also the preservation of cultural identity and social cohesion.

In conclusion, the Guna people’s relocation due to rising sea levels is a poignant reminder of the urgent need to address climate change.

By learning from their experience and adopting a holistic approach to resettlement, other communities at risk can stand a better chance of overcoming the adverse effects of climate change while preserving their cultural heritage and social fabric.